Apple has revealed its first Mac computers powered by chips of its own design.

In June, the company announced it would transition away from the Intel processors it had used since 2006.

Apple said the advantages of using the M1 chip included better battery life, instant wake from sleep mode, and the ability to run iOS apps.

It added it had optimised all of its own Mac apps, but now needs to convince other developers to do likewise.

The new computers include new versions of its:

- 13in (33cm) MacBook Air, which no longer requires a fan to keep its processor cool

- 13in MacBook Pro, which Apple said can now play video for 20 hours on a single battery charge – twice as long as before. It keeps its fan

- Mac Mini screen-less desktop computer

Apple’s website indicates this will be the only type of MacBook Air it sells from now on, but it will continue to offer the other two machines with Intel chips as an option.

It did not unveil new versions of its iMac or Mac Pro computers, suggesting Apple might be waiting for more advanced versions of the chip with more memory and greater graphics-processing capabilities to use in those.

The new Macs will go on sale next week. They will run the MacOS Big Sur operating system, which will be released to existing Intel-based Macs this Thursday.

Customised chip

Apple claimed the M1 can deliver the peak performance of the “latest PC laptop chip” while using just a quarter of the power, or be made to deliver twice the CPU (central processing unit) performance.

But one downside is the Macs now only come with up to 16 gigabytes of memory.

That is half the amount of Ram the Intel-based version of the MacBook Pro offers and one quarter the amount the equivalent Mini goes up to. Video editing software and games are among apps that typically benefit from having more memory.

Apple’s chips are sometimes referred to as being Arm-based because it licenses the instruction sets – which determine how processors handle commands – from a UK-based company called Arm.

But the core processor circuits are of the American company’s own design.

One advantage is that Apple gets control over which accelerators to include. These are special sections that specialise at handling certain tasks such as machine learning or cryptography.

It also gets to integrate memory and other functions into a single package, instead of using other specialist chips, which should contribute to performance gains.

“The move to Apple silicon allows Apple to get the same level of integration we have seen on iOS and iPadOS where the user gets the benefit of having an operating system and app ecosystem that are optimised to the silicon,” explained Carolina Milanesi from the consultancy Creative Strategies.

Another benefit is that iPhone and iPad apps can be run on the processor, although they are likely to need a user-interface redesign to work without a touchscreen,

The downside is that existing apps, which were written for Intel processors, will need to be run under emulation.

Apple suggests its Rosetta 2 emulator will translate these on the fly without problem, but the software will only run as fast and smoothly as it can if developers take the time to update their products to run natively.

Despite recent tensions with its developers community, one expert predicted most consumer apps would soon be adapted, but added that it could be a different matter for some more specialist programs.

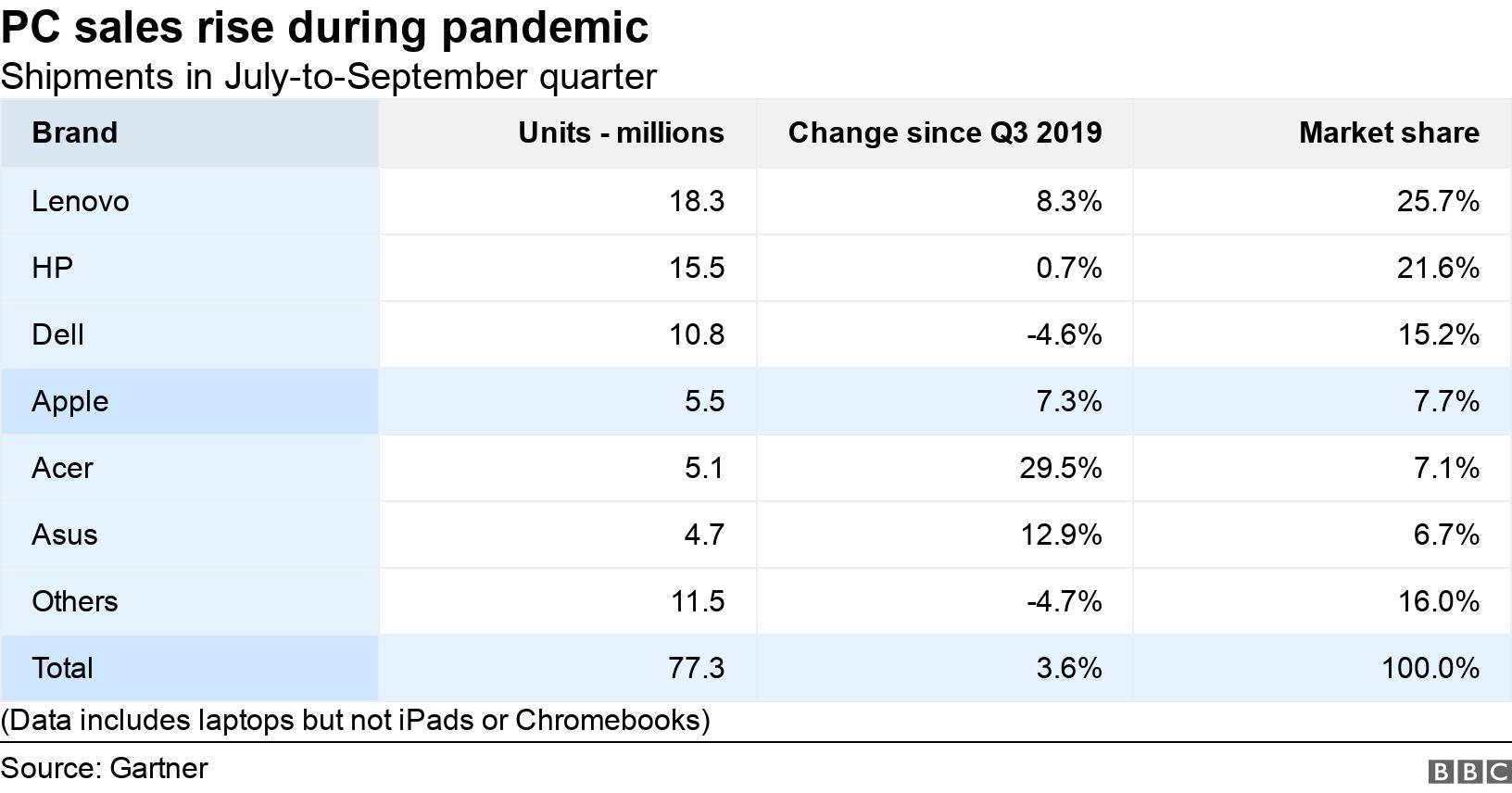

“Apple is one of the top five players in the PC market, but it faces an issue in enterprise, because there its share is only about 5%,” commented Annette Jump from Gartner.

“And it could find it much harder to convince software-makers focused on that sector to start developing their products for the new Macs.”

Apple said Adobe would release a native version of Photoshop next year, and Omni Group would also publish universal versions of its productivity software.

But there was no mention of Microsoft’s Office apps or a way to run Windows 10 natively.

Surface rival

Microsoft has also done much work to get Windows to run on Qualcomm’s Arm-based chips – which were also originally designed for mobile phones.

It released one such device, the Surface Pro X, earlier this year, taking advantage of the low-power processor to produce its “thinnest” model yet.

But for now, the bulk of Windows computer sales remain reliant on Intel’s technology, although there is speculation that the new Macs could have knock-on effects.

“Apple’s moves will help validate Arm-based chips for personal computing and even in the data centre, meaning the whole Arm ecosystem will benefit,” said Ben Wood from CCS Insight,

“This, rather than the loss of the Mac business, is the longer-term concern for Intel.”

Landmark Macintosh computers

The Mac is one of the oldest surviving computer brands. While it has typically been outsold by cheaper PCs, at least some of its variations have been hugely influential.

Apple Macintosh (1984)

The iconic all-in-one personal computer was not Apple’s first to offer a mouse-controlled graphical user interface (GUI) – the Lisa achieved that a year earlier. But it did so at about a quarter of the cost.

The original Macintosh model had a very limited amount of memory and was unable to use a hard disc. Some of those sacrifices mmeant a more capable follow-up had to be rushed out the same year.

Macintosh II (1987)

The first Macintosh to support use of a colour display.

It also introduced the “chimes of death” sound, which played if a hardware fault was detected.

Macintosh Portable (1989)

Although the original Macintosh had a handle at its back to help carry it about, this was the firm’s first computer to be powered by a battery.

It lasted about 10 hours on a charge – but its bulk and high-price prevented it selling well.

Apple continued to use built-in trackballs on its laptops until it shifted to trackpads in 1994.

Powerbook Duo (1992)

For five years, Apple sold a range of relatively lightweight and compact laptops that were designed to be plugged into a dock and used with a larger monitor, floppy disc drive and external keyboard when at home or work.

But the “ultraportable”concept was arguably ahead of its time and flopped.

Power Macintosh 6100 (1994)

Apple’s first major jump in processor technology, when it switched from Motorola’s 68k-series chips to the PowerPC processors that it co-developed with Motorola and IBM.

The shift meant existing software had to be run under emulation, causing it to run more slowly until it was rewritten for the chip’s reduced instruction set computer (Risc)-based architecture.

iMac G3 (1998)

The computer presented a fresh take on what a home PC could look like, and helped save Apple from bankruptcy.

It bore the influence of both Steve Jobs – who had returned as chief executive – and Jony Ive, who had become the company’s industrial design chief.

The G3 designation was added to its name once a model with a faster PowerPC chip launched.

Power Mac G4 Cube (2000)

Another attempt to restyle computing, but this one failed to catch on. For its price, its performance and poor upgradability were seen by many as too limited – and it didn’t help that some users complained of cracks appearing in its plastic casing.

Tim Cook later said “we put a lot of love into it”… but it was a “spectacular failure commercially”.

Powerbook G4 (2001)

Originally encased in a titanium body, the laptop introduced a design that has evolved and endured over the years.

The lack of a Powerbook G5 replacement became a long-running joke, as Motorola struggled and ultimately failed to design a version of its chip that would run cool enough to fit in the machine.

Mac Mini (2005)

A compact desktop PC that was originally designed to be an entry-level computer for those on a tight budget who could re-use an existing monitor and other peripherals.

Later models were also marketed for use as computer servers for small businesses.

iMac (2006)

Apple’s first computer to feature Intel processors.

Older software again had to be run under emulation, this time using the first version of Apple’s Rosetta software, which could translate code written for G3 and G4 – but not G5 – chips into instructions the Intel chip could handle.

MacBook Air (2008)

Steve Jobs famously unveiled what was “the world’s thinnest laptop” by removing it from a paper envelope.

It was originally marketed as a being premium product before dropping to become the design of the firm’s entry-range laptops.

MacBook Pro (2016)

The laptop introduced the touch bar – an interactive control strip that offering an alternative to fixed standard function keys.

The bar is powered by its own Arm-based processor.

Mac Pro (2019)

The redesigned high-end desktop tower helped reaffirm Apple’s commitment to the Mac platform.

And the fact that its optional pack of add-on wheels costs an extra £700 serves as a reminder that the firm believes there is a market for computers that command a premium for design and not just power.

BBC